Jim Webber with Matt Cloyd: The Power of Graph in Conflict Resolution

Chief Scientist, Neo4j

10 min read

At this year’s NODES event, Jim Webber – Neo4j’s Chief Architect and CTO – wrapped up the day with an enthralling series of interviews with customers and community members. His keynote showcased the stories of four different Neo4j users, each of whom had their own unique path to graph.

In the second of these keynote interviews, Matt Cloyd took the virtual stage and spoke with Jim about his work at the intersection of civic technology and graphs. He also shared an exciting project on his horizon in the space of conflict resolution and politically-related violence – which certainly sounds very promising for the greater good of all.

Check out the talk Jim did with Asurion’s Julie Fisher earlier, and stay tuned for more of these interviews in the coming weeks.

Enjoy!

Meet Civic Technologist Matt Cloyd

Jim Webber: I’m thrilled to announce my second guest for today’s closing keynote. Matt Cloyd, you have been in the Neo4j community for a long time now. In the preamble that we had before the closing keynote, we were reminiscing about folks that we have in common in this community. What I’d like to start with, you work on kind of the overlay of civic tech and graphs. Could you tell us a bit about what that means?

Matt Cloyd: Sure. So civic technology – the way that I think about it – is using the right size dose of technology to help local communities deal with some kind of issue. I really got my start in Code for Boston. And so it was just a small group of people at first, maybe five or 10 people, but we ended up growing to sometimes 50 people in a meeting in a community of hundreds of people who were all interested in using either technology skills, or technology adjacent skills like design systems, thinking research, etc. to actually partner with the towns in and around Boston. We wanted to work with government officials to – I think at the core of it – improve the relationship between government and constituents to increase people’s trust in government by helping government be better public servants and really worthy of that trust. So it’s really all about relationship building. And actually, the timing for this interview is great, because this week I started a position as a consulting engineer with 18F, which is one of the U.S. federal digital agencies.

Jim Webber: That’s fantastic. Congratulations.

Matt Cloyd: Thank you.

Jim Webber: Sorry to be interrupting you in your first week.

How Does He Use Graph Technology As a Civic Tech Practitioner?

Matt Cloyd: Oh no, this is a good little break in all the orientation training. Yeah, and so graphs have come in for me. So one of the most influential books that I’ve ever read is this really massive textbook called Design for Ecological Democracy. And it covers kind of the intersection between environmental sustainability, interpersonal equity, and democracy as a whole. And one of the really powerful concepts in there for me was the idea of power mapping specifically looking at a particular issue in a community and saying, okay, well who has the power to change this, and who is connected to them, and who can I talk to, to talk to, to talk to in order to maybe make some kind of meaningful change here? So that was definitely one of my inspirations in kind of getting into graphs to begin with.

Jim Webber: That’s an interesting observation, right? That notion of, how do I connect to power and what influence can I exert down that path in order to change things hopefully for the better? So, I mean, it’s obvious to me now that that’s a graph problem. Was it obvious to you and your team of civic minded techs and tech-adjacents that it was a graph problem?

Matt Cloyd: I don’t know that that was immediately obvious. I think it was only when I stumbled upon graph databases and other graph-related concepts in my casual computing education that the two of those really clicked together.

Jim Webber: Interesting. So good fortune brought you this way then. That’s good to know. I think we could all do with a dose of good fortune. So it sort of starts to make sense to me a little bit now, because you said you were working with tech folks. I think tech folks are quite comfortable with graph tech nowadays. It’s certainly far more humane than when I first started. And even Neo4j was this Java Plus Maven hellscape. It is like zero point X versions. And I think actually nowadays, it’s very humane, and Cypher is very humane and productive for those of us with a modestly technical background. But you’ve gone a step further, right? With a language called Aspen, which is specifically designed to be even more humane. Could you tell us a bit about that?

Coding with Apsen and Cypher to Get Results

Matt Cloyd: Sure. So Aspen at its core is sort of designed to be the markdown of creating graph data. It’s not a query language. And even though Cypher is a little clunky if you’re trying to generate graph data, it is an incredibly elegant query language. So Aspen isn’t trying to query. It’s just trying to generate the graph data.

And this came out of a course that I took in the fall of 2019. So after working in civic tech for awhile, I decided to get a master’s in conflict resolution, because I was interested in getting a little bit deeper into community decision-making and how to resolve conflicts, and make decisions in ways that promote equity and peace. And in my first class, the kind of conflict theory overview class, one day we had an activity to go on the whiteboard and just model all of the factors and parties in a conflict. And as we started whiteboarding, I went, oh, that looks like a graph. I’m going to see as – somebody else is scribing on the whiteboard – I’m gonna see on my laptop if I can just pop this into Neo4j. And then wouldn’t that be interesting, to have a computable analyzable graph of the conflict? And I wonder if there are things that we could do with network analysis and other things there.

So I start typing and I start writing the Cypher directly into the browser console. And I’m finding that I have to do very specific things with, kind of, making sure the entities exist, and having everything in the right order, and remembering what all the nicknames are. And I started to get a little bit frustrated. And so I started sketching a language – what would it look like to just be able to take notes about a conflict? Like, let’s say I was a researcher in a conflict zone and I just wanted to understand how this person is related to that person, and how this person is related to that community leader. Kind of the power mapping thing, but from a slightly different angle.

I started writing the code that I wished to write and then found a few amazing blog posts on how to write a simple language. I’m not a language person. Like, I write Ruby-based web applications. I don’t write languages. And so this just ended up being really a simple language right now entirely written in Ruby that takes very simple notes about relationships and then you just add parentheses to entities or nodes, square brackets to the edges or relationships, and Aspen will turn that into Cypher and pop it into Neo4j on your behalf.

Jim Webber: Oh, that’s wonderful. In fact, as you’re telling that tale like so many similar stories, I was hooked by the David Easley and Jon Kleinberg book, Networks, Crowds, and Markets. And in one of the chapters there, they actually have the starting point for World War I as a graph. And they show how it evolved from three emperors’ leagues creating triangles of friendships and enemies. And they said, “Hey, look, and it evolves into WWI.” And that blows me away, right? That graphs can do that.

It strikes me also given the modern times and the ongoing culture war, which is a peculiar kind of conflict. Aspen in particular could be helpful for your neighbor in the Northeast, Sophie Hill, who’s a political scientist at Harvard. She runs a system called My Little Crony, which is a delightful pun. I think something like Aspen would be the kind of thing that our political scientists could use to start to make sense of well, who’s voting for who, who’s taking a buck for who, who gets a contract once they’re elected, and all that kind of stuff. I think that’s a phenomenal way of opening up graph tech to people who are specialists in other areas, right? As you say, it’s the kind of thing that I could write in a Moleskine book, and then miraculously get a graph from it. That’s astounding. I love it.

So you had this thing when you were relatively new to graphs – when you were trying to follow people and type Cypher – you ended up inventing a new DSL for graphs. That’s pretty ambitious. Is there anything from your experience that you would say to people like your previous self, relatively new to graphs, who have an inkling of what they can do, and want to be involved? I mean, what would your letter to previous you be to help you get going?

Words of Wisdom He Would Impart on a Young Matt

Matt Cloyd: So I think just getting a warm welcome into the community really was a big start. It was that – and reading a couple books on graph theory – really how I got started. And yeah, I don’t even clearly remember how I got involved in the community. I feel like somebody from the community itself – I wanna say Michael Hunger – emailed me about something randomly one day. Yeah. And I didn’t know who this was, but he just provided this warm welcome and then got me connected with a few other people.

And I really want to express my gratitude for the – until recently (now the former) community manager – Karin [Wolok]. She was just so welcoming and engaging. And I assume that she was like this for everybody who attended NODES last year, but she just was like, “Come on in, share what you’ve got to share, be a part of this.” So I guess my advice would really just be to jump into the community, meet people through whatever means. People tend to be really genuinely friendly and helpful.

Jim Webber: Yeah, I found that right. I think, for a lot of things in Neo4j business, we always want them to kind of change, right? I think often we want them to grow, right? Community size – even we’d like that to grow. I think one thing that’s been remarkably constant in the community, even as it has grown enormously, is everyone’s still really nice, right?

Matt Cloyd: Yeah.

Jim Webber: It’s one of the nicest tech communities I’ve ever been in. There’s not the kind of argumentativeness that seems to permeate a lot of communities. It’s very helpful. And me too actually – whenever I want to know answers to stuff that’s not apparent to me, I drop into the community. There’s always someone who will help me, which I should perhaps be embarrassed about, but I’m not, I love it. The community’s ace. So given the community’s got your back, so to speak, I hope you’re going to do more stuff with graphs. Where do you think graphs are going to go in your part of the world in civic tech and so on?

Graphs for the Future of Conflict Resolution

Matt Cloyd: I don’t know if I can predict anything generally speaking, but one project I have on the horizon is that I’m finishing up my master’s degree in conflict resolution this summer, and I’m doing work with a group through the Center for Peace, Democracy, and Development at UMass Boston to essentially develop what we believe is the country’s first early warning and early response system for politically related violence. So kind of like looking at all of the events in the U.S. over the last year, and drawing on the expertise of people who have done conflict forecasting and prevention work in other countries around the world.

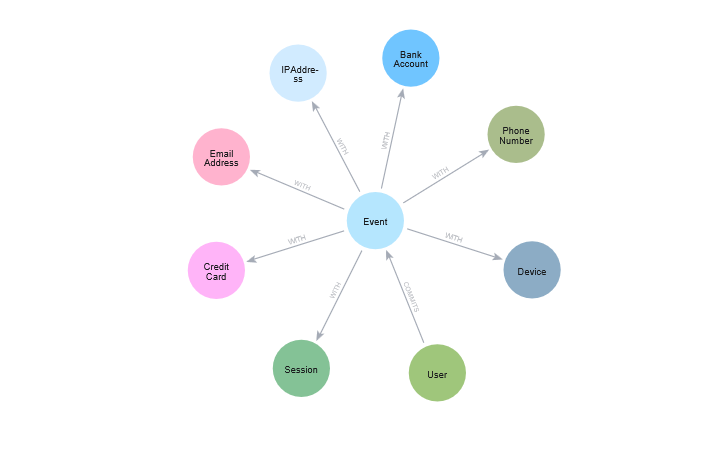

We’re looking at using graphs as one of several different models for basically pulling in data, and trying to forecast, and hopefully intervene in possible political conflicts. So right now, we’re at the very, very early stages. Like we’re just getting formed, just starting out. We haven’t yet used graphs for analysis, but we are doing what I think is really interesting, kind of almost philosophical work, because we want to be analyzing data at the city or the metropolitan statistical area level.

And that is more granular analysis than we have found in our literature review so far. There might be people out there, but we haven’t seen anybody doing this. And so we’re looking at things like the interactions and the chains of events that are happening in say, Portland, Oregon, protests night after night, after night after night – who are the actors there? How are they interacting? What is the quality of their interactions? Is that escalating or de-escalating larger conflicts? And so we’re having to do a lot of thought around, how do we model things like this in a graph database for analysis? And we don’t have any of the answers to that yet, but it’s really interesting conceptual work. And I think, six to 12 months from now, my hope is that we’re going to have a graph-based analysis that possibly helps forecast – maybe not perfectly – but helps forecast conflictual events that can be intervened in and de-escalated before it turns into violence.

Jim Webber: Wow, that is an incredibly useful case. Well, Matt, thank you for joining us today. It’s been wonderful to host you virtually. I hope our paths will cross physically again in the future. Thank you so much for taking time out of your master’s thesis, your new job, and an enormous analysis project. So I truly appreciate it. Good luck for the future, and thanks once again.

Matt Cloyd: Thank you so much.