How to Import the Bitcoin Blockchain into Neo4j [Community Post]

learn me a bitcoin

8 min read

[As community content, this post reflects the views and opinions of the particular author and does not necessarily reflect the official stance of Neo4j.]

This guide runs through the basic steps for importing the bitcoin blockchain into a Neo4j graph database.

The whole process is just about taking data from one format (blockchain data), and converting it into another format (a graph database). The only thing that makes this slightly trickier than typical data conversion is that it’s helpful to understand of the structure of bitcoin data before you get started.

However, once you have imported the blockchain into Neo4j, you can perform analysis on the graph database that would not be possible with SQL databases. For example, you can follow the path of bitcoins to see if two different addresses are connected:

Screenshot of connected Bitcoin Addresses in the Neo4j Browser.

In this guide I will cover:

- How bitcoin works, and what the blockchain is.

- What blockchain data looks like.

- How to import the blockchain data into Neo4j.

This isn’t a complete tutorial on how to write your own importer tool. However, if you’re interested, you can find my bitcoin-to-neo4j code on GitHub, although I’m sure you could write something cleaner after reading this guide.

1. What Is Bitcoin?

Bitcoin is a computer program.

It’s a bit like uTorrent; you run the program, it connects to other computers running the same program, and it shares a file. However, the cool thing about bitcoin is that anyone can add data to this shared file, and any data already written to the file cannot be tampered with.

As a result, Bitcoin creates a secure file that is shared on a distributed network.

What can you do with this?

In bitcoin, each piece of data that gets added to this file is a transaction. Therefore, this decentralised file is being used as a “ledger” for a digital currency (i.e., cryptocurrency).

This ledger is called the blockchain.

Where can I find the blockchain?

If you run the Bitcoin Core program, the blockchain will be stored in a folder on your computer:

- Linux:

~/.bitcoin/blocks - Windows:

~/Library/Application Support/Bitcoin/blocks - Mac:

C:\Users\YourUserName\Appdata\Roaming\Bitcoin\blocks

When you open this directory you should notice that instead of one big file, you will find multiple files with the name blkXXXXX.dat. This is the blockchain data, but split across multiple smaller files.

2. What Does the Blockchain Look Like?

The blk.dat files contain serialized data of blocks and transactions.

Blocks

Blocks are separated by magic bytes, which are then followed by the size of the upcoming block.

Each block then begins with a block header:

A block is basically a container for a list of transactions. The header is like the metadata at the top.

Block Header Example:

000000206c77f112319ae21489b66774e8acd379044d4a23ea7498000000000000000000821fe1890186779b2cc232d5dbecfb9119fd46f8a9cfd1141649ff1cd907374487d8ae59e93c011832ec0399

Transactions

After the block header, there is a byte that tells you the upcoming number of transactions in the block. After that, you get serialized transaction data, one after the other.

A transaction is just another piece of code again, but they are more structurally interesting.

Each transaction has the same pattern:

- Select Outputs (we call these Inputs).

- Unlock these inputs so that they can be spent.

- Lock these outputs to a new address.

So after a series of transactions, you have a transaction structure that looks like something this:

This is a simplified diagram of what the blockchain looks like. As you can see, it looks like a graph.

Transaction Example:

0200000001f2f7ee9dda0ba82031858d30d50d3205eea07246c874a0488532014d3b653f03000000006a47304402204df1839028a05b5b303f5c85a66affb7f6010897d317ac9e88dba113bb5a0fe9022053830b50204af15c85c9af2b446338d049672ecfdeb32d5124e0c3c2256248b7012102c06aec784f797fb400001c60aede8e110b1bbd9f8503f0626ef3a7e0ffbec93bfeffffff0200e1f505000000001976a9144120275dbeaeb40920fc71cd8e849c563de1610988ac9f166418000000001976a91493fa3301df8b0a268c7d2c3cc4668ea86fddf81588ac61610700

3. How to Import the Blockchain into Neo4j

Well, now we know what the blockchain data represents (and that it looks a lot like a graph), we can go ahead and import it into Neo4j. We do this by:

- Reading through the

blk.datfiles. - Decoding each block and transaction we run into.

- Converting the decoded block/transaction into a Cypher query.

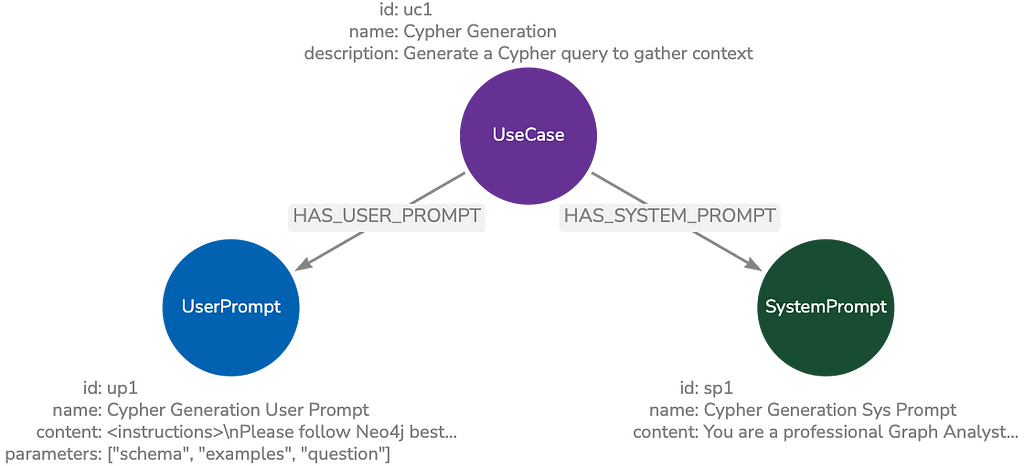

Here’s a visual guide to how I represent Blocks, Transactions and Addresses in the database:

Blocks

- CREATE a

:blocknode, and connect it to the previous block it builds upon.- SET each field from the block header as properties on this node.

- CREATE a

:coinbasenode coming off each block, as this represents the “new” bitcoins being made available by the block.- SET a value property on this node, which is equal to the block reward for this block.

Transactions

- CREATE a

:txnode, and connect it to the:blockwe had just created.- SET properties (version, locktime) on this node.

- MERGE existing

:outputnodes and relate them[:in]to the:tx.- SET the unlocking code as a property on the relationship.

- CREATE new

:outputnodes that this transaction creates.- SET the respective values and locking codes on these nodes.

Addresses

If the locking code on an :output contains an address…

- CREATE an

:addressnode, and connect the output node to it.- SET the address as a property on this node.

- Note: If different outputs are connected to the same address, then they will be connected to the same address node.

4. Cypher Queries

Here are some example Cypher queries you could use for the basis of inserting blocks and transactions into Neo4j.

Note: You will need to decode the block headers and transaction data to get the parameters for the Cypher queries.

Block

MERGE (block:block {hash:$blockhash})

CREATE UNIQUE (block)-[:coinbase]->(:output:coinbase)

SET

block.size=$size,

block.prevblock=$prevblock,

block.merkleroot=$merkleroot,

block.time=$timestamp,

block.bits=$bits,

block.nonce=$nonce,

block.txcount=$txcount,

block.version=$version,

MERGE (prevblock:block {hash:$prevblock})

MERGE (block)-[:chain]->(prevblock)

Parameters (example):

{

"blockhash": "00000000000003e690288380c9b27443b86e5a5ff0f8ed2473efbfdacb3014f3",

"version": 536870912,

"prevblock": "000000000000050bc5c1283dceaff83c44d3853c44e004198c59ce153947cbf4",

"merkleroot": "64027d8945666017abaf9c1b7dc61c46df63926584bed7efd6ed11a6889b0bac",

"timestamp": 1500514748,

"bits": "1a0707c7",

"nonce": 2919911776,

"size": 748959,

"txcount": 1926,

}

Transaction

MATCH (block :block {hash:$hash})

MERGE (tx:tx {txid:$txid})

MERGE (tx)-[:inc {i:$i}]->(block)

SET tx += {tx}

WITH tx

FOREACH (input in $inputs |

MERGE (in :output {index: input.index})

MERGE (in)-[:in {vin: input.vin, scriptSig: input.scriptSig, sequence: input.sequence, witness: input.witness}]->(tx)

)

FOREACH (output in $outputs |

MERGE (out :output {index: output.index})

MERGE (tx)-[:out {vout: output.vout}]->(out)

SET

out.value= output.value,

out.scriptPubKey= output.scriptPubKey,

out.addresses= output.addresses

FOREACH(ignoreMe IN CASE WHEN output.addresses <> '' THEN [1] ELSE [] END |

MERGE (address :address {address: output.addresses})

MERGE (out)-[:locked]->(address)

)

)Note: This query uses the FOREACH hack, which acts as a conditional and will only create the :address nodes if the $addresses parameter actually contains an address (i.e., if it is not empty).

Parameters (example):

{

"txid":"2e2c43d9ef2a07f22e77ed30265cc8c3d669b93b7cab7fe462e84c9f40c7fc5c",

"hash":"00000000000003e690288380c9b27443b86e5a5ff0f8ed2473efbfdacb3014f3",

"i":1,

"tx":{

"version":1,

"locktime":0,

"size":237,

"weight":840,

"segwit":"0001"

},

"inputs":[

{

"vin":0,

"index":"0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000:4294967295",

"scriptSig":"03779c110004bc097059043fa863360c59306259db5b0100000000000a636b706f6f6c212f6d696e65642062792077656564636f646572206d6f6c69206b656b636f696e2f",

"sequence":4294967295,

"witness":"01200000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000"

}

],

"outputs":[

{

"vout":0,

"index":"2e2c43d9ef2a07f22e77ed30265cc8c3d669b93b7cab7fe462e84c9f40c7fc5c:0",

"value":166396426,

"scriptPubKey":"76a91427f60a3b92e8a92149b18210457cc6bdc14057be88ac",

"addresses":"14eJ6e2GC4MnQjgutGbJeyGQF195P8GHXY"

},

{

"vout":1,

"index":"2e2c43d9ef2a07f22e77ed30265cc8c3d669b93b7cab7fe462e84c9f40c7fc5c:1",

"value":0,

"scriptPubKey":"6a24aa21a9ed98c67ed590e849bccba142a0f1bf5832bc5c094e197827b02211291e135a0c0e",

"addresses":""

}

]

}

5. Results

If you have inserted the blocks and transactions using the Cypher queries above, then these are some examples the kind of results you can get out of the graph database.

Block

MATCH (block :block)<-[:inc]-(tx :tx) WHERE block.hash='$blockhash' RETURN block, tx

Transaction

MATCH (inputs)-[:in]->(tx:tx)-[:out]->(outputs) WHERE tx.txid='$txid' OPTIONAL MATCH (inputs)-[:locked]->(inputsaddresses) OPTIONAL MATCH (outputs)-[:locked]->(outputsaddresses) OPTIONAL MATCH (tx)-[:inc]->(block) RETURN inputs, tx, outputs, block, inputsaddresses, outputsaddresses

Address

MATCH (address :address {address:'1PNXRAA3dYTzVRLwWG1j3ip9JKtmzvBjdY'})<-[:locked]-(output :output)

WHERE address.address='$address'

RETURN address, output

Paths

Finding paths between transactions and addresses is probably the most interesting thing you can do with a graph database of the bitcoin blockchain, so here are some examples of Cypher queries for that:

Between Outputs

MATCH (start :output {index:'$txid:vout'}), (end :output {index:'$txid:out'})

MATCH path=shortestPath( (start)-[:in|:out*]-(end) )

RETURN path

Between Addresses

MATCH (start :address {address:'$address1'}), (end :address {address:'$address2'})

MATCH path=shortestPath( (start)-[:in|:out|:locked*]-(end) )

RETURN path

Conclusion

This has been a simple guide on how you can take the blocks and transactions from blk.dat files (the blockchain) and import them into a Neo4j database.

I think it’s worth the effort if you’re looking to do serious graph analysis on the blockchain. A graph database blockchain is a natural fit for bitcoin data, whereas using an SQL database for bitcoin transactions feels like trying to shove a square peg into a round hole.

I’ve tried to keep this guide compact, so I haven’t covered things like:

- Reading through the blockchain. Reading the blk.dat files is easy enough. However, the annoying thing about these files is that the blocks are not written to these files in sequential order, which makes setting the height on a block or calculating the fee for a transaction a bit trickier (but you can code around it).

- Decoding blocks and transactions. If you want to use the Cypher queries above, you will need to get the parameters you require by decoding the block headers and raw transaction data as you go. You could write your own decoders, or you could try using an existing bitcoin library.

- Segregated Witness. I’ve only given a Cypher query for an “original” style transaction, which was the only transaction structure used up until block 481,824. However, the structure of a segwit transaction is only slightly different (but it might need its own Cypher query).

Nonetheless, hopefully this guide has been somewhat helpful.

But as always, if you understand how the data works, converting it to a different format is just a matter of sitting down and writing the tool.

Good luck.

Click below to get your free copy of the Learning Neo4j ebook and catch up to speed with the world’s leading graph database technology.