Creating a Knowledge Graph From Video Transcripts With ChatGPT 4

Graph ML and GenAI Research, Neo4j

13 min read

Use GPT-4 as a domain expert to help you extract knowledge from a video transcript.

A couple of days ago, I got access to GPT-4. The first thing that came to my mind was to test how well it performs as an information extraction model, where the task is to extract relevant entities and relationships from a given text. I have already played around with GPT-3.5 a bit. The most important thing I noticed is that we don’t want to use the GPT endpoint as an entity linking solution or have it come up with any other external references like citations, as it likes to hallucinate those types of information.

However, a great thing about GPT-3 or GPT-4 is that it performs well in various domains. For example, we can use it to extract people, organizations, or locations from a text. However, I feel that competing against dedicated NLP models is not where the GPT models shine (although they perform well). Instead, the strength of GPT models is in their ability to generalize and be used in other domains where other open-sourced models fail due to their limited training data.

My friend Michael Hunger gave me a great idea to test the GPT-4 on extracting information from a nature documentary. I always liked the deep sea documentary as the ecosystem and animals are so vastly different from terrestrial ones. Therefore, I decided to test GPT-4 information extraction capabilities on an underwater documentary. Additionally, I don’t know of any open-source NLP models trained to detect relationships between sea plants and creatures. So, a deep sea documentary makes for an excellent example of using a GPT-4 to construct a knowledge graph.

All the code is available on GitHub in a form of a Jupyter notebook.

Dataset

The most accessible place to find documentaries is YouTube. Although the GPT-4 is multi-modal (supports video, audio, and text), the current version of the endpoint only supports text inputs. Therefore, we will analyze a video’s audio transcript, not the video itself.

We will be analyzing the transcript of the following documentary.

First of all, I like the topic of the documentary. Secondly, extracting captions from a YouTube video is effortless as we don’t have to use any audio2text models at all. However, converting audio to text with all the available models on HuggingFace or even OpenAI’s Whisper shouldn’t be a big problem. Thirdly, this video has captions that are not auto-generated. At first, I tried to extract information from auto-generated captions on YouTube, but I learned that they might not be the best input. So if you can, avoid using auto-generated YouTube captions.

The captions can be retrieved straightforwardly with the YouTube Transcript/Subtitle library. All we have to do is to provide the video id.

from youtube_transcript_api import YouTubeTranscriptApi

video_id = "nrI483C5Tro"

transcript = YouTubeTranscriptApi.get_transcript(video_id)

print(transcript[:5])The transcript has the following structure

[

{

"text":"water the liquid that oceans are made of",

"start":5.46,

"duration":4.38

},

{

"text":"and it fills endless depths only few will venturexa0xa0",

"start":12.24,

"duration":4.92

},

{

"text":"out into the endless open oceanxa0nof this vast underwater world",

"start":17.16,

"duration":4.68

}

]The captions are split into chunks, which can be used as video subtitles. Therefore, the start and duration information is provided along with the text. You might also notice a couple of special characters like xa0 and n .

Even though GPT-4 endpoint support up to 8k tokens per request, more is needed to process the whole transcript in a single request. Therefore, we need to split the transcript into several parts. So, I decided to split the transcript into multiple parts, where the end of the part is determined when there are five or more seconds of no captions, announcing a brief pause in narration. Using this approach, I aim to keep all connecting text together and retain relevant information in a single section.

I used the following code to group the transcript into several sections.

# Split into sections and include start and end timestamps

sections = []

current_section = ""

start_time = None

previous_end = 0

pause_threshold = 5

for line in transcript:

if current_section and (line["start"] - previous_end > pause_threshold):

# If there is a pause greater than 5s, we deem the end of section

end_time = line["start"]

sections.append(

{

"text": current_section.strip(),

"start_time": start_time,

"end_time": end_time,

}

)

current_section = ""

start_time = None

else:

# If this is the start of a new section, record the start time

if not start_time:

start_time = line["start"]

# Add the line to the current paragraph

clean_text = line["text"].replace("n", " ").replace("xa0", " ")

current_section += " ".join(clean_text.split()) + " "

# Tag the end of the dialogue

previous_end = line["start"] + line["duration"]

# If there's a paragraph left at the end, add it to the list of paragraphs

if current_section:

end_time = transcript[-1]["start"] + transcript[-1]["duration"]

sections.append(

{

"text": current_section.strip().replace("n", " ").replace("xa0", " "),

"start_time": start_time,

"end_time": end_time,

}

)

# Remove empty paragraphs

sections = [p for p in sections if p["text"]]To evaluate results of the section grouping, I printed the following information.

# Number of paragraphs

print(f"Number of paragraphs: {len(sections)}")

print(f"Max characters per paragraph: {max([len(el['text']) for el in sections])}")There are 77 sections, with the longest having 1267 characters in it. We are nowhere near the GPT-4 token limit, and I think the above approach delivers a nice text granularity, at least in this example.

Information Extraction With GPT-4

GPT-4 endpoint is optimized for chat but works well for traditional completion tasks. As the model is optimized for conversation, we can provide a system message, which helps set the assistant’s behavior along with any previous messages that can help keep the context of the dialogue. However, as we are using the GPT-4 endpoint for a text completion task, we will not provide any previous messages.

I used the following prompt as the system message.

system = "You are an archeology and biology expert helping us extract relevant information."However, I noticed that the model behaved almost identically when I provided the system message or not. Next, I developed the following prompt through some iterations, which extracts relevant entities and relationships from a given text.

# Set up the prompt for GPT-3 to complete

prompt = """#This a transcript from a sea documentary.

#The task is to extract as many relevant entities to biology, chemistry, or archeology.

#The entities should include all animals, biological entities, locations.

#However, the entities should not include distances or time durations.

#Also, return the type of an entity using the Wikipedia class system and the sentiment of the mentioned entity,

#where the sentiment value ranges from -1 to 1, and -1 being very negative, 1 being very positive

#Additionally, extract all relevant relationships between identified entities.

#The relationships should follow the Wikipedia schema type.

#The output of a relationship should be in a form of a triple Head, Relationship, Tail, for example

#Peter, WORKS_AT, Hospital/n

# An example "St. Peter is located in Paris" should have an output with the following format

entity

St. Peter, person, 0.0

Paris, location, 0.0

relationships

St.Peter, LOCATED_IN, Parisn"""The GPT-4 is prompted to extract relevant entities from a given text. Additionally, I added some constraints that distances and time durations should not be treated as entities. The extracted entities should contain their name, type, and the sentiment. As for the relationships, they should be provided in a form of a triple. I added some hints that the model should follow Wikipedia schema type, which makes the extracted relationship types a bit more standardized. I learned that it is always good to provide an example of an output as otherwise the model might use different output formats at will.

One thing to note is that we might have instructed the model to provide us with a nice JSON representation of extracted entities and relationships. Nicely structured data might certainly be plus. However, you are paying the price for nicely structured JSON objects as the cost of the API is calculated per input and output token count. Therefore, the JSON boilerplate comes with a price.

Next, we need to define the function that calls the GPT-4 endpoint and processes the response.

@retry(tries=3, delay=5)

def process_gpt4(text):

paragraph = text

completion = openai.ChatCompletion.create(

model="gpt-4",

# Try to be as deterministic as possible

temperature=0,

messages=[

{"role": "system", "content": system},

{"role": "user", "content": prompt + paragraph},

],

)

nlp_results = completion.choices[0].message.content

if not "relationships" in nlp_results:

raise Exception(

"GPT-4 is not being nice and isn't returning results in correct format"

)

return parse_entities_and_relationships(nlp_results)Even though we explicitly defined the output format in the prompt, the GPT-4 model sometimes does its own thing and does not follow the rules. It happened to me only twice out of a couple of hundred requests. However, it is annoying when that happens, and all the downstream dataflow doesn’t work as intended. Therefore, I added a simple check of the response and added a retry decorator in case that happens.

Additionally, I only added the temperature parameter to make the model behave as deterministic as possible. However, when I rerun the transcript a couple of times, I got slightly different results. It costs around $1.6 to process the transcript of the chosen video with GPT-4.

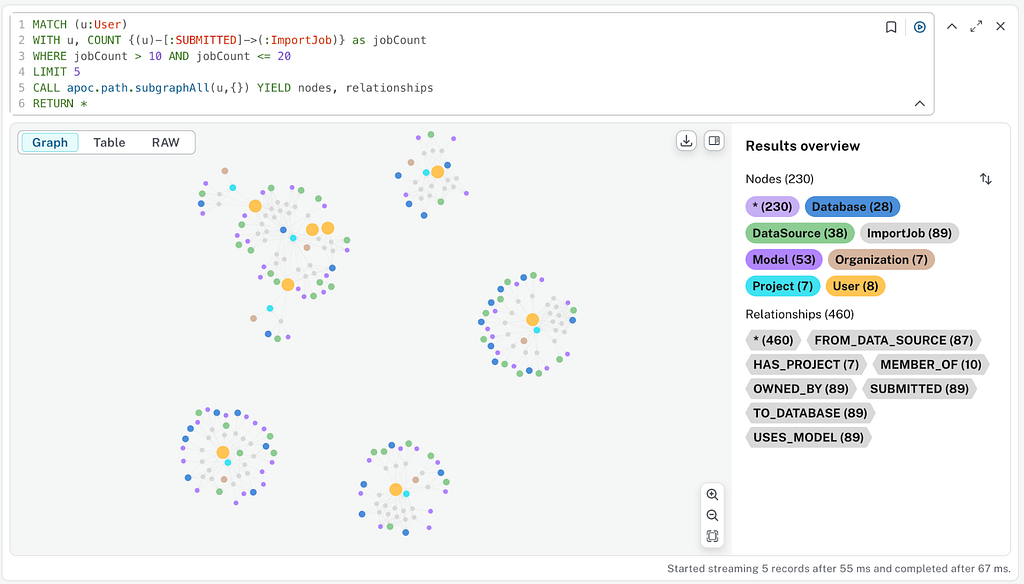

Graph Model and Import

We will be using Neo4j to store the results of the information extraction pipeline. I have used a free Neo4j Sandbox instance for this project, but you can also use the free Aura, or local Desktop environment.

One thing is certain. No NLP model is perfect. Therefore, we want all extracted entities and relationships to point to the text where they were extracted, which allows us to verify the validity of information if necessary.

Since we want to point the extracted entities and relationships to the relevant text, we need to include the sections along with the video in our graph. The section nodes contain the text, start, and end time. Entities and relationships are then connected to the section nodes. What might be counterintuitive is that we represent extracted relationships as a node in our graph. The reason is that Neo4j doesn’t allow to have relationships to point to another relationship. However, we want to have a link between extracted relationship and its source text. Therefore, we need to model the extracted relationship as a separate node.

The Cypher statement for the graph import is the following:

import_query = """

MERGE (v:Video {id:$videoId})

CREATE (v)-[:HAS_SECTION]->(p:Section)

SET p.startTime = toFloat($start),

p.endTime = toFloat($end),

p.text = $text

FOREACH (e in $entities |

MERGE (entity:Entity {name: e[0]})

ON CREATE SET entity.type = e[1]

MERGE (p)-[:MENTIONS{sentiment:toFloat(e[2])}]->(entity))

WITH p

UNWIND $relationships AS relation

MERGE (source:Entity {name: relation[0]})

MERGE (target:Entity {name: relation[2]})

MERGE (source)-[:RELATIONSHIP]->(r:Relationship {type: relation[1]})-[:RELATIONSHIP]->(target)

MERGE (p)-[mr:MENTIONS_RELATIONSHIP]->(r)

"""Finally, we can go ahead and process the whole transcript and import the extracted information into Neo4j using the following code:

with driver.session() as session:

for i, section in enumerate(sections):

print(f"Processing {i} paragraph")

text = section["text"]

start = section["start_time"]

end = section["end_time"]

entities, relationships = process_gpt4(text)

params = {

"videoId": video_id,

"start": start,

"end": end,

"text": text,

"entities": entities,

"relationships": relationships,

}

session.run(import_query, params)You can open Neo4j Browser and validate the import by executing the following Cypher statement.

CALL apoc.meta.graph()The meta graph procedure should return the following graph visualization.

Entity Disambiguation With GPT-4

After inspecting the GPT-4 results, I have decided that performing a simple entity disambiguation would be best. For example, there are currently five different nodes for a Moray Eels:

- moray eel

- Moray

- Moray Eel

- moray

- morays

We could lowercase all entities and use various NLP techniques to identify which nodes refer to the same entities. However, we can also use the GPT-4 endpoint to perform entity disambiguation. I wrote the following prompt to perform entity disambiguation.

disambiguation_prompt = """

#Act as a entity disambiugation tool and tell me which values reference the same entity.

#For example if I give you

#

#Birds

#Bird

#Ant

#

#You return to me

#

#Birds, 1

#Bird, 1

#Ant, 2

#

#As the Bird and Birds values have the same integer assigned to them, it means that they reference the same entity.

#Now process the following valuesn

"""The idea is to assign the same integers to nodes that refer to the same entity. Using this prompt, we are able to tag all nodes with additional disambiguation property.

def disambiguate(entities):

completion = openai.ChatCompletion.create(

model="gpt-4",

# Try to be as deterministic as possible

temperature=0,

messages=[

{"role": "user", "content": disambiguation_prompt + "n".join(all_animals)},

],

)

disambiguation_results = completion.choices[0].message.content

return [row.split(", ") for row in disambiguation_results.split("n")]

all_animals = run_query("""

MATCH (e:Entity {type: 'animal'})

RETURN e.name AS animal

""")['animal'].to_list()

disambiguation_params = disambiguate(all_animals)

run_query(

"""

UNWIND $data AS row

MATCH (e:Entity {name:row[0]})

SET e.disambiguation = row[1]

""",

{"data": disambiguation_params},

)Now that the disambiguation information is in the database, we can use it to evaluate the results.

MATCH (e:Entity {type:"animal"})

RETURN e.disambiguation AS i, collect(e.name) AS entities

ORDER BY size(entities) DESC

LIMIT 5Results

While this disambiguation is not that complicated, it is still worth noting that we can achieve this without NLP knowledge or having to develop any hand-crafted rules.

Analysis

In the final step of this blog post, we will evaluate the results of the information extraction pipeline using the GPT-4 model.

First, we will examine the type and count of extracted entities.

MATCH (e:Entity)

RETURN e.type AS type, count(*) AS count

ORDER BY count DESC

LIMIT 5Results

Most entities are animals, locations, and biological entities. However, we can notice that sometimes the model decides to use the whitespace and other times underscore for biological entities.

Throughout my experiments with GPT endpoints, I have observed that the best approach is to be as specific as possible in what information and how you want it to be categorized. Therefore, it is good practice with GPT-4 to define the types of entities we want to extract, as the resulting types will be more consistent.

Additionally, the model didn’t classify 33 entity types. The thing is that GPT-4 might come up with some types for these entities if asked. However, they only appear in the relationship extraction part of the results, where entity types are not requested. One workaround could be to ask for entity types in the relationship extraction part as well.

Next, we will examine which animals are the most mentioned in the video.

MATCH (e:Entity {type:"animal"})

RETURN e.name AS entity, e.type AS type,

count{(e)<-[:MENTIONS]-()} AS mentions

ORDER BY mentions DESC

LIMIT 5Results

The most mentioned animals are moray eels, lionfish, and brittle stars. I am familiar only with eels, so watching the documentary to learn about other fishes might be a good idea.

We can also evaluate which relationships or facts have been extracted regarding moray eels.

MATCH (e:Entity {name:"morays"})-[:RELATIONSHIP]->(r)-[:RELATIONSHIP]->(target)

RETURN e.name AS source, r.type AS relationship, target.name AS target,

count{(r)<-[:MENTIONS_RELATIONSHIP]-()} AS mentions

UNION ALL

MATCH (e:Entity {name:"morays"})<-[:RELATIONSHIP]->(r)<-[:RELATIONSHIP]-(source)

RETURN source.name AS source, r.type AS relationship, e.name AS target,

count{(r)<-[:MENTIONS_RELATIONSHIP]-()} AS mentionsResults

There is quite a lot we can learn about moray eels. They cooperate with groupers, coexist with Triggerfishes, and are being cleaned by cleaner shrimps. Additionally, a moray searching for a female moray can be relatable.

Let’s say, for example, we want to check if the relationship that morays interact with lionfish is accurate. We can retrieve the source text and validate the claim manually.

MATCH (e:Entity)-[:RELATIONSHIP]->(r)-[:RELATIONSHIP]->(t:Entity)

WHERE e.name = "morays" AND r.type = "INTERACTS_WITH" AND t.name = "Lionfish"

MATCH (r)<-[:MENTIONS_RELATIONSHIP]-(s:Section)

RETURN s.text AS textResults

ly tough are its cousins the scorpion fishes they

lie there as if dead especially when others around

them freak out and even when moray eels fight with lionfishes for foodThe text mentions that eels fight with lionfish for food. We can also notice that the transcript is hard to read and understand, even for a human. Therefore, we can commend GPT-4 for doing a good job on a transcript where even a human might struggle.

Lastly, we can use the knowledge graph as a search engine that returns timestamps of sections where relevant entities we want to see. So, for example, we can ask the database to return all the timestamps of sections in which lionfish is mentioned.

MATCH (e:Entity {name:"Lionfish"})<-[:MENTIONS]-(s:Section)<-[:HAS_SECTION]-(v:Video)

RETURN s.startTime AS timestamp, s.endTime AS endTime,

"https://youtube.com/watch?v=" + v.id + "&t=" + toString(toInteger(s.startTime)) AS URL

ORDER BY timestampResults

Summary

The remarkable ability of GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 models to generalize across various domains is a powerful tool for exploring and analyzing different datasets to extract relevant information. In all honesty, I’m not entirely sure which endpoint I would use to recreate this blog post without GPT-4. As far as I know, there are no open-source relation extraction models or datasets on sea creatures. Therefore, to avoid the hassle of labeling a dataset and training a custom model, we can simply utilize a GPT endpoint. Furthermore, I’m eagerly anticipating the opportunity to examine its promised capability for multi-modal analysis based on audio or text input.

As always, the code is available on GitHub.

Thinking about building a knowledge graph?

Download The Developer’s Guide: How to Build a Knowledge Graph for a step-by-step walkthrough of everything you need to know to start building with confidence.